😸 Github

Everything you *didnt know* about the Github Story. How pending a lifetime in debt lead to bootstrapping a hybrid company for four years plus a deep dive into seeding a networks effects business.

Hello folks 👋,

Last week I went viral on Twitter which as many of you know, has been a lifelong dream of mine. Over 1 million impressions 👇🏽. I saw a lot of familiar names in there…so thank you for the support <3.

I also ran a quick Twitter poll on what developer company I should write about this week, and over 50% of you voted for Github.

As a democratically run newsletter, I have decided to do just that…so without further ado (I know its 4 days late…sorry about that🙈) I would like to welcome you to the First 1000 x Github case study 😉.

To all my non-developers out there

At its core, Github is the Google docs for developers. It allows developers to collaborate, share and maintain code-bases at scale. But in reality, it is much more than that. It is an App store for code, the resume for a developer, and the social network where they share their inventions with the world.

The Github story is unique in many ways:

🦄 In 2018, Github became the third-largest acquisition ever made by Microsoft, sitting at $7.5b (after Skype and Linkedin)

🏝They moved from a remote-first company in 2008 to a Hybrid company in 2010 and made it work 🤷♂️. This was well before Hybrid was even a term.

💳 They bootstrapped the company for 4 years and scaled it to over 3 million repos (aka projects) before raising any venture money.

But before diving into the company, let's take a look at the mastermind behind it. Enter Tom Preston-Werner.

The year was 1999

Tom is not your typical had-lemonade-stand-when-I-was-3-years-old entrepreneur. His first real stab at building a company came during his Sophomore year at Harvey Mudd University, when his summer internship turned into a full-time job offer as a Java developer. Tom faced the dilemma of dropping out to become an employee for a hot tech company (right before the Dotcome bubble burst) or go back to school for two years only to find himself looking for a similar position in the foreseeable future… he took the job....and boy, was it the wrong move🙈.

The Dotcom burst.

Shortly after, the Dotcom bubble burst and the company Tom was working for got acquired in a fire sale. Tom was let go (RIP Good times🧟♂️)

Tom and a couple of his buddies, who were also let go during this terrible time, teamed up to start a tech consultancy business called Cube6 Media, paying homage to the cube number Tom had during his short-lived developer career. Cube6 Media did a little bit of everything; you wanted to do flyers, they got you, you needed a new website, they got you, you needed a media strategy...guess what they got you.

This broad focus, coupled with the fact that the oldest person working at the agency was a 22-year-old programmer, meant that businesses wasn’t exactly rushing through the Cube6 door. His other two friends/cofounder had the foresight to leave Cube6 Media to get "real jobs," but Tom decided to persevere through it and fly solo...and boy was it the wrong move (yet again).

Racking off debt.

The three years that followed were a struggle. By the end of year 1, Tom thought that he was doing OK...only to get hit by a $23k tax bill(as a sole proprietorship, you are supposed to pay estimated taxes every month), but this 22 years old business owner had no freakin clue as to what he was doing. By the end of year 3, Tom was $50k in debt, mainly to the IRS and the eight credit card companies he used to make ends meet throughout.

The surmounting debt was not enough of a reason for the hot-headed entrepreneur to throw in the towel, he had one last trick up his sleeves...take on MORE DEBT.

At that time, in 2003-2004, the housing market was on 🔥. Every month real-estate prices were going up, banks were incentivizing consumers to take on loans with the introduction of No-Document-Loans, and just like stonks today...real estate only went up and to the right (🐶TO THE MOOOOON).

It so happens that Tom’s landlord was selling the property he was renting, and Tom’s solution to the $50k debt problem was to take on some Equity debt: debt that theoretically can appreciate in value faster than the interest. The idea was to use some that upside from the equity(i.e increase in home value) to pay off his $50k bill. The housing market was not so generous to Tom in the following years, but in 2006 he refinanced his mortgage (just in the nick of time) and used some cashback from the refinancing to pay off some of his credit card debt. Finally a small win after years of struggle!

Throwing in the towel

In parallel as Tom was working on his consultancy business, the Ruby on Rails movement was just starting to gain traction.

This new framework enamored Tom; he was an active member of the RoR San Diego community and advocated for its use in every new project he took on at Cube6 media. But, unfortunately, traditional companies weren't interested in using the new shiny framework that just came out...they wanted the old and tested.

This is what pushed Tom over the edge to give up on Cube6 Media; it wasn't the debt or the fact that three years in, it was not working. Instead, he wanted to work with Ruby on Rails, and the consultancy clients just weren't ready.

Gravatar

As Ruby on Rails was gaining popularity among developers faster than a snowcone melting in hell, Tom started to dapple with it on the side. Every few weeks, he would go to the San Diego Ruby on Rails meetups to catch up with some other developers. From time to time, people presented what they were working on. The most promising Ruby On Rails project Tom was working on and brought forth to this community was called Gravatar.

Gravatar was an avatar that tracked you across the internet. Every time you create an account on a website that uses Gravatar, it will capture your avatar from the service. If you change it on one website, it updates it on all of them. Pretty simple, pretty neat.

The only problem was, it wasn't making any money. It was your typical kickstarting a network effects business dilemma. Companies did not find significant value from being early adopters to Gravatar. The real value of Gravatar came when they are integrated with a statistically significant portion of the web. And until Tom could hit that critical mass, monetization was mission impossible.

Gravatar slowly grew to over 32,000 users, and so did the operational overhead. By the end of 2006, Tom had to spend 2-3 hours a day manually approving the 300-400 new Gravatar profile pictures that got uploaded that day.

Attempt 1: trying to offload Gravatar.

The motivating factor to keep going with Gravatar was that Tom saw it as the gateway from the crippling debt. If someone out there could find some value from this global profile picture service, just $50k worth of value, all his problems would be solved; he could finally be a DEBT-FREE man.

On top of his hit list for companies that he could potentially acquire Gravatar was Automattic, the parent company behind WordPress.

Believe it or not, Blogging was still a thing in 2006, and not having empty/default profile pictures on the 99% of the blog posts comment was a reasonable enough value proposition for the company...or so Tom thought. So through his Ruby on Rails meetups connections, he managed to set up a meeting with the Exec team at Automattic in SF.

Bay Area for life

A few weeks later, Tom flew to SF, unfortunately though, the meeting did not go as well as Tom had hoped. Automattic was intrigued but not that interested in acquiring Gravatar.

The one good thing that came out of this trip was Tom's friends (also a Ruby on Rails fanatic) urging him to go for a hail-marry interview at the new hot company he just joined Powerset.

Powerset was a natural language processing search company that had the ambition to be the next Google. What they did, which was novel at the time, was very similar to Google Answer Snippets. They surfaced more in-depth answers to your questions, considering the context in a much better way than Google did (or so made their claim go). It's not every day you get a company that, not only dares to challenge Google in their core product: Search, but also gets the backing and stamp of approval from one of Silicon Valley's legendary figures: Peter Thiel (Cofounder and ex-CEO of Paypal).

Tom took the meeting and after a couple of rounds of interviews, he would score the second small win in his life: getting a stable source of income. Accepting the job wasn’t as straightforward of a choice as you might imagine. Sure, Cube6 Media was struggling and never really took off, but Tom had just invested all this money he never had in a buying a home he couldn't afford. To add salt to injury, he thought he would close the Gravatar transaction during this trip and decided to invest even more money he didn’t have into renovating the kitchen and floors of the house.

With this new job prospect as a Junior Software Developer at Powerset, he would have to give up his business, and by some miracle, finish renovating the house by himself as he can no longer afford contractors (he never could actually, I dk what he was thinking 🧐). He concluded the timing didn't align, and decided to go back to San Diego and try to grind at Cube6 Media for a few more years.

In a typical Netflix-rom-com moment, shortly after Tom arrived at the airport, he had his anti-climatic "aha" moment and got in a cab and blewoff his flight. Over the next few days, he would go back to Powerset and negotiate a start date 3 months out. That way, he would have enough time to wrap up all loose ends in his consultancy business and try to pull a miracle out of his 🍑 in finishing up his kitchen and floor renovations by himself so that he could rent out his place in San Diego. This was the only way to make ends meet between his debt payments, property taxes, and junior developer salary.

Three months later, Tom moved from San Diego to the Bay Area to join Powerset, and his life would change forever.

One thing ends, another begins.

Six months into this new job, Tom reaches out to Automattic again in an attempt to finally crush that debt and sell his side-hustle Gravatar. I am not sure how the conversation went or what exactly changed their minds, but they finally agreed to acquire the company, and on October 18th, 2007, Tom announced to the world via a Wordpress blog post that Gravatar had been acquired. For the first time since 1999, Tom had a net worth of >$0. The only caveat here is that the banks have foreclosed on his San Diego property along the way during that time, but that is neither here nor there. TOM WAS A FREE MAN.

In the months prior, as the transaction was coming to a close, Tom did not spend any time 🍆ing around...the next side-project was already brewing inside this beautiful brain.

"I think I was sitting at the booth alone because I'd just ordered a fresh Fat Tire and needed a short break from the socializing that was happening over at the long tables in the dimly lit aft portion of the bar. On the fifth or sixth sip, Chris Wanstrath walked in. I have trouble remembering now if I'd even classify Chris and I like "friends" at the time. We knew each other through Ruby meetups and conferences, but only casually. Like a mutual "hey, I think your code is awesome" kind of thing. I'm not sure what made me do it, but I gestured him over to the booth and said, "dude, check this out." About a week earlier, I'd started work on a project called Grit that allowed me to access Git repositories in an object-oriented manner via Ruby code. Chris was one of only a handful of Rubyists at the time that was starting to become serious about Git. He sat down, and I started showing him what I had. It wasn't much, but it was enough to see that it had sparked something in Chris. Sensing this, I launched into my half-baked idea for some website that acted as a hub for coders to share their Git repositories. I even had a name: GitHub. I may be paraphrasing, but his response was along the lines of a very emphatic "I'm in. Let's do it!"

Tom Co-founder of Github

Brief Detour: History of Git

It is worthwhile to spend a minute to unpack this sentence. "Chris was one of only a handful of Rubyists at the time that was starting to become serious about Git." In 2007, Git was the shiny new thing, developed only a couple of years earlier by Linus Torvalds, the main developer behind the Linux Kernel and the "godfather" of open-source software.

The history of Git is fascinating.

Back in 2005, if developers wanted to collaborate on code, they had two choices of version control software.

Client-Server Model: This meant there was only one central repository where all the code lived and everyone worked. This structure meant projects were heavily gated by maintainers of the code. If you wanted to contribute to an open-source project, it was as much as "who you knew" as it was how good your code/contribution is. That "walled-garden" model made it hard to collaborate on large-scale projects.

Distributed Model: This meant that everyone could have their version of the code and work on it collaboratively. The only problem was that the leading players in the distributed version control software charged a lot of $$$ for their service.

The Linux Kernel project was managed using one of these the leading distributed version control software at the time named Bitkeeper. Linus Torvalds managed to secure an agreement for a free license for his open-source project the Linus Kernet. But in 2005, probably some MBA Biz Ops person crunched his numbers and decided that the company can no longer subside the Linus free-riders. And so Bitkeeper reneged on their free license.

Linus took this personally, and instead of shopping around for yet another for-profit version control software, he created his own: a better, open-source, free version control software named Git. Rumor has it that Linus and the core contributors to Linux built Git in a single week, but 🤷♂️.

Git was significant for many reasons. Primarily because the godfather of open-source himself developed it. More importantly, though, it was a big _|_ from the open-source community to the for-profit companies. Using Git, developers can create branches, fork(copy) projects, work on multiple versions simultaneously, then elegantly pull all the code together in one master file something that was not easily do-able with Bitkeeper.

Back to the story

Git was what you would call a Cult business similar to Tesla, Roam, or even Atoms. For the people who mastered it, they thought it was the best thing ever happened to the internet since the internet was invented. Still, for everyone else, they couldn't wrap their heads as to why those people were swearing by it.

Tom and Chris saw the Cult behind Git forming, sure it would take some time for it to be widely adopted, but they thought if they could build "the easiest" way to host Git Repos and just waited for Git to gain adoption, they could capitalize on all the free distribution that came from it.

The popularity in their minds was inevitable; the most intelligent people in their Ruby communities (Chris included) already spent the time to learn Git and unlock its superpowers. There was no turning back for those folks; it was only a matter of time until all developers would realize what they already did: Git is Bae.

Building Github

On October 19th, 2007, Chris and Tom pushed the first commit to Github. It was, by all means, a side-project. Not because they did not have enough conviction in the idea but rather that they knew it would be a while before Git gained adoption, and building on top of a nascent platform would take time to materialize. This is the tradeoff of being an early-mover in a space, you get to capture a significant portion of the demand, but the market is tiny. In VC terms...the TAM did not exist for Github at this point.

That sat well with Tom and Chris. For starters, Tom was still working at Powerset, a hot VC-backed company, and was in no rush to leave his cushy job for another entrepreneurial stunt after what he had gone through with Cube6 Media and Gravatar. On the other hand, Chris was working at CNET, and being a Git + Ruby on Rails fanatic meant that the thrill of building technology at the intersection of his interests was so worth it...even if it would never materialize into something more than a weekend project. He was already spending too much time working on Git-related side projects, and Github was the most ambitious version of them all combined.

Fun Fact: The development of Github started just one day after Tom announced the acquisition of Gravatar (even though the deal likely took place a few months earlier). Sit and Wait

"I don't expect GitHub to succeed right away. Git adoption will take a while, but we'll be ready when it happens."

- Tom Cofounder of Github

The problem with taking this sit-and-wait-for-Git-to-be-popular approach meant that the duo couldn't raise significant dollars for the project, and hosting software costs a bag loads of monies. So they leaned into their Ruby on Rails community and got connected to web hosting company Engine Yard. They struck a deal for free hosting in exchange for a footer banner promoting the company.

Hosting companies wanted to reach developers building significant projects, Github enabled developers to work on big projects seamlessly, a better match couldn't be made in heaven.

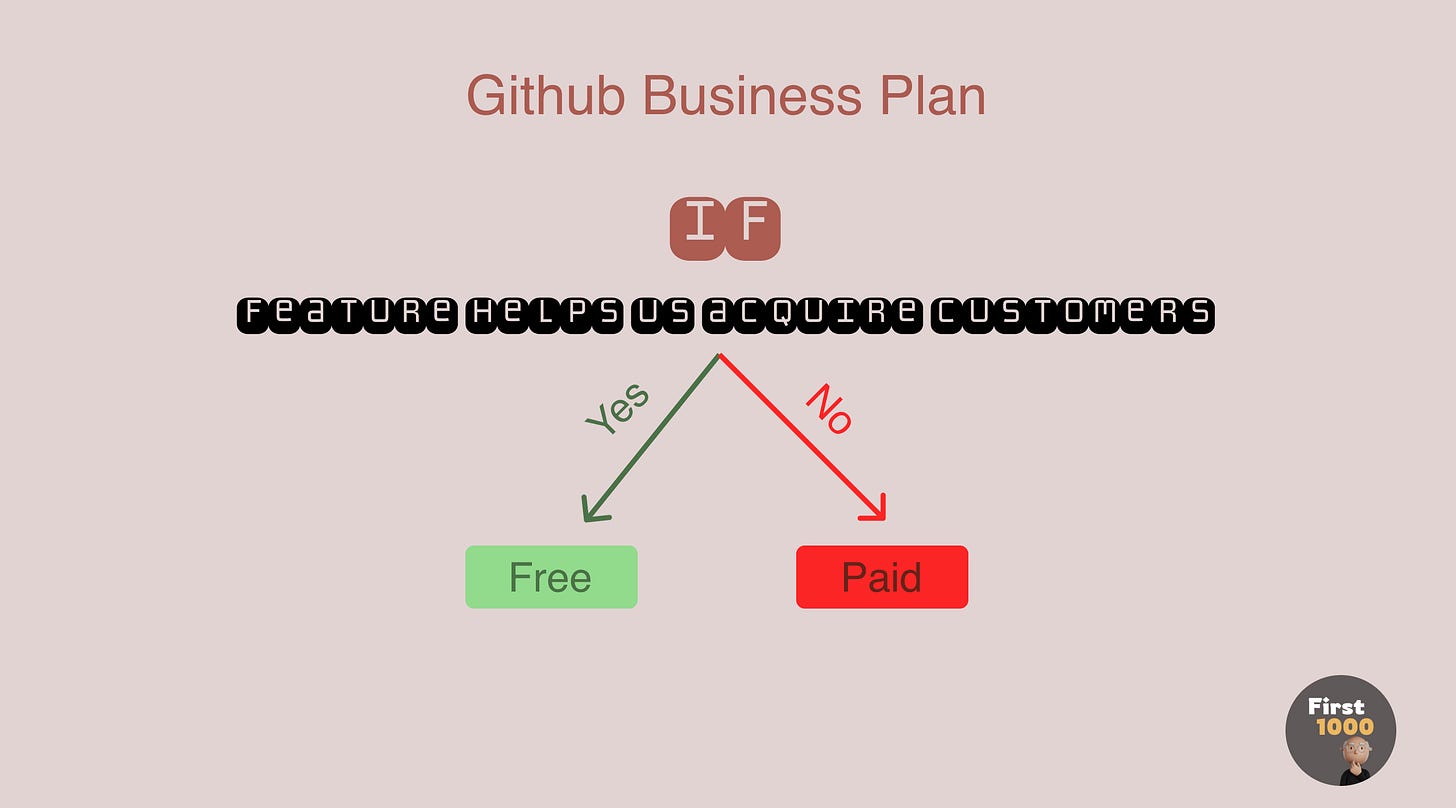

The second problem that came from the sit and wait approach was monetization. Tom, after being burnt with never being able to monetize Gravatar, and their rightful but completely wrong prediction that Github would be popular by the adoption of Git and not the other way round, they needed to sustain the project until this distant time in the future. So the two not-business entrepreneurs came up with a business model that would render the $250k price tag on MBAs a scam.

Acquiring Customers:

Now that the duo got the fundamentals covered and started working on the Facebook+Linkedin+Google docs+Squarespace+App Store for developers, let’s spend a minute diving deep into the growth loop that comes from the network effects of Github.

Unlike many of its Web 2.0 counterparts, GitHub had an effective business model. Simply, GitHub provides companies and programmers a choice: they can use the collaborative platform for free as a place to build open-source software, or pay to use it as closed-source software, where they can program proprietary code that creates part of a commercial product. In the first instance, your goodwill to make your code available to everyone awards you the opportunity to take advantage of the army of open-source coders working on the GitHub platform. In the second, your company's programmers work in confidential, utilizing the collaborative tools GitHub has created but not its dispersed global force of talent. In the same breath, GitHub is like a junkyard and assembly line. Programmers on the platform can go pick out, or help develop, pretty much all of the open-source raw materials they need to build their product and set up their own closed work space to integrate those materials with their existing products.

The more open-source projects that are hosted on the website, the bigger the Github army of open-source developers, the more utility that Github provides to the open-source and the more reason for people to choose to host their projects on Github.

Seeding the network

While network effects are interesting in theory, it’s useless unless you manage to seed this network to a critical volume. There are some things they intentionally did, and others that were just a byproduct of the nature of Github in order to get there.

1️⃣ Let's start with the latter :

🎮Single-Player Mode

In a gross-generalization, every network effects business started off with a great single-player utility. In many instances, this discovery was by accident, ( i.e Kevin Systrome and IG, when his girlfriend pointed him in the direction of filters.) In the case of Github, the single-player mode, was the ability to easily manage and host your Git side-projects. Even if all the collaboration tools don't make sense to you, using Github to host your project was still X10 easier than setting up your own servers.

🎮🎮Low Threshold Multi-Player mode

The network effects for Github users were two-layered, both play off each other, but each pay off their dividends(value) separately. The first layer of network effects occurs when you invite your team or collaborators to join the project hosted on Github, and as benefit from the ease of collaboration. For this layer achieving critical mass, was fairly easy, if you work with those people elsewhere, they are just an email invite away

The second layer comes from attracting new contributors to your project through Github. This one had a much higher threshold to critical mass, but as more people utilized the first collaboration layer and onboarded their team to Github , the second one became more powerful as the combination of these mini-networks of teams created this giant network of open-source developers on Github.

So even the "multi-player" mode had a shallow threshold for critical mass, at least for the first collaboration layer.

2️⃣ As for what they actually did to seed the network:

📪 Emailing Ruby on Rails Friends

This one is pretty obvious, Tom and Chris met through a Ruby on Rails, heard and got excited about Git through that same community. Unsurprisingly, their first course of action was emailing people they got to know over the past 3 years from being members there, inviting them to the private Beta that would make managing Git Projects a Breeze 🌬.

👨🏻💻Tom's Open-Source Projects

Grit

If you recall, what prompted this whole Github project was the open-source library Tom created Grit that allowed users to access Git repositories in an object-oriented manner via Ruby code. Another Ruby + Git fanatics match made in heaven. Tom of course, hosted Grit on Github which meant as this library gained traction within the Ruby and Git cults, they got to discover Github.

God (and no not THAT God)

This was another open-source project Tom was working on during his time at Powerset (where he was still employed during this time). God was another Ruby project that was gaining heavy momentum within the Ruby community.

Tom used his own somewhat popular open-source projects to piggyback distribution to Github, pretty ingenious if you ask me.

🧨 First *Big* Project

The first big project that came onboard to Github was Merb, which later merged with Ruby on Rails. Merb was an open-soure project developed by Engine Yard the hosting partner for Github.

Engine Yard having struck a free "distribution" deal with Github had a lot to gain from the popularity and legitimization of the "side-project." The had a lot to gain from building this massive open-source project on Github and seeding the platform with , probably, hundreds of developers work. The power of aligned incentives can not be understated here.

🍺 Drinkups

At the beginning of the Github journey, they relied heavily on the Ruby on Rails meetups. But as the product grew, Github needed to change the narrative of these meetups from revolving around Ruby to revolving around Github.

The only problem was, without critical mass, it is really hard to find a hard-core group of people who would be willing to block time off their calendar to physically commute to a location to geek out about a product still in beta.

So, instead of rallying people behind Github, they rallied them behind 🍻 . If developer conferences were Coachella, Drinkups were the secret VIP after-parties you never got invited to. Tom and Chris invested every extra $$ they had in buying developers beers after any major tech/developer conference....courtesy of Github of course😬.

Free Beer was an easier sell than a hosting solution to an emerging tech built for the hard-core open-source community.

🪞 Mirroring

The last lever was mirroring. Big open-source still had to be hosted somewhere, the problem is that you had to put in the effort to find them across the internet manually.

Github centralized these decentralised open-source projects, and many of the early projects hosted on Github were mirrors of existing projects. (As in, there was a little bit of code that ran every hour/day/week..etc that would go and check a particular popular open-source project, and if there were any changes made it to it, it would apply the same changes to the "mirrored" codebase on Github.) Everyone could use Github to find an up to date version of this popular open-source project, copy it over and built on top of it easily.

Making Money

Github reached 1000 repos (projects) in the first 2 months of its 3 months private beta. What Tom and Chris didn't realize at the time they started, was that Github's main value proposition was not the hosting part, but rather unlocking the power of Git to novice developers. Github was what Git needed for mass adoption and not vice versa.

By April 2008, Github launched to the public having gotten over 2,000 projects onboard in the private Beta, Chris received this message from Geoffrey Grosenbach, founder of online learning site PeepCode, which had just migrated its code to GitHub.

This is when the duo would go on to recruit the third Cofounder Pj Hyett to build the billing system. On the first day they launched the paid product, Github made $1000 dollars. Not enough for Tom and Chris to quit their full-time jobs, but enough to know there is something there.

8 months into starting Github, Powerset was acquired by Microsoft for $100m. Faced between a $300k bonus (over three years) and a taking out a junior developer salary from the money Github was making at the time, Tom decided to go fulltime on Github, (and so did the other two cofounders.) And I am so grateful they did, I couldn’t even fathom a world without Github today.

This is it for today, and I hope you enjoyed this one 😉.

See you next Sunday,

P.S: I am revamping the website. Sorry in advance for any glitches you may or may not face with the referral program and the delays with the Shoutout requests from May. It’s happening I promise, just hammering out a couple of analytics issues.😬