💳 Stripe

Everything you didn't know about the Stripe 0->1000 story

Hello Frens 👋,

Today I’m bringing back one of the first issues published for First 1000 from the archives. It’s the story of Stripe

Let’s start from the very very beginning

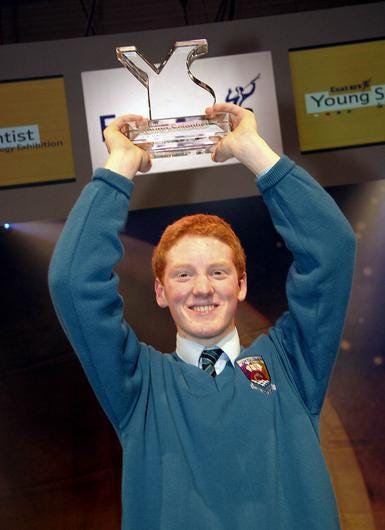

In 2005, sixteen-year-old Patrick Collison (Patrick is the cofounder of Stripe) did what many high school nerds do and participated in the Young Scientist Of The Year competition. Unlike in other parts of the world, where people build volcanos and stuff, this competition was the shit in Ireland….like many notable tech breakthroughs came out of there.

Okai..so why is that important 🤷♂️?

Patrick won the competition, but in retrospect, for someone who built a $95b+ company in his twenties (and early thirties now 👴🏼)…that should come as no surprise. The important bit was that during this competition, Patrick first encountered Common Lisp (a dialect of the Lisp programming language), and one of the biggest Lisp fans on this planet is Paul Graham.

Throughout his time in the competition, Patrick spent a lot of time contributing to Lisp. As a young teen, he leveraged it to build his app “Isaac” (his entry to the competition). Isaac is what we would call today a chatbot….in 2005, chatbots weren’t a thing….and building one with some basic machine learning running in the background was enough to grant him the winning Prize.

Patrick moves to the US to attend MIT (2007)

After winning the competition, Patrick was admitted to MIT at 17, 1.5 years before finishing high school. 🙀 (talk about being smart). His brother John, who is two years younger, was on his “activation year.” Activation year is an Irish concept where students take a year off between middle and high school to explore…well life. Students are expected to get some work experience, or travel or contribute to society in some shape or form…because there is more to life than just your grades (as a student…I approve of this message🧑🏽⚖️).

Moving back to Ireland

In his “activation year,” John started tinkering around with the idea of creating a better eBay. The idea was to create a mix of Wikipedia and eBay. Patrick being a good brother, decided to lend him a hand. After the first quarter of his freshman year at MIT, Patrick gained so much conviction in this project that he moved back to 🇮🇪🇮🇪 to be with his little bro and continue working on the project full time and dropped from MIT (technically, he took a leave of absence)

Getting into YC and moving to Silicon Valley

Even though Patrick was 17 and John was only 15, they got accepted into the fourth ever batch of YC (W07). The only reason Patrick and John, two teenagers from rural Ireland knew anything about YC was because of Patrick’s involvement with Lisp during his science competition the year prior. Their app “Shuppa” merged with another YC company as soon as they joined. The combined company was named Auctomatic, and the brothers got back to working hard.

Auctomatic and becoming teen millionaires (March 2008)

The ambition for Auctomatic was to build the next eBay. Still, they started off with tools that help individual sellers on sites such as eBay, Amazon, Overstock, and others manage their listings. In 2008 eBay was all the rave and within a few months of launching, the Auctomatic team got their first acquisition offer. They were young and naive and thought they “had a much larger vision,” so they didn’t entertain it, but over the next 3 months, they got 4-5 more offers and the teens caved in (I guess everyone has a price). They sold the company 11 months in for $5m 🤑.According to media Gossip from 2008, each of the Collison brothers netted around $1.2m from that deal and overnight became self-made teen millionaires.

The return to normal

In case you weren’t already feeling bad about yourself (I know I was), let me remind you that John Collison became a millionaire at 15 during his gap year and went back to Ireland to *start* his high school.

Patrick, on the other hand, moved to 🇨🇦🇨🇦🇨🇦 to work as the Director of Engineering at “Live Current Media” the public company that acquired Auctomatic. Patrick spent a year in Canada (maybe that was a part of the deal…maybe not…we will never know 🥴). After the year ended, Patrick decided to re-enroll at MIT and officially start his second year. Since he joined the university 1.5 years younger than everyone else…he figured he wasn’t in a real rush to graduate.

Stripe…the first lines of code (October 2009)

So at the age of 19, after going to MIT, then back to Ireland, then to SF, then to Canada, and finally back to MIT (gotta respect the hustle), Patrick started working on the first version of Stripe. To be fair, though, he was working on SO MANY DIFFERENT THINGS at that time. After going through the rollercoaster of founding and selling a company in less than a year and encountering a sort of normalcy of being a student, the guy just had to tinker away….I guess MIT was too boring for him.

Patrick was working on hacking an offline version of Wikipedia for the iPhone (before Apple allowed apps on the app store) + a better web framework for Common Lisp. During that time, Patrick became obsessed with Slicehost. Slicehost…is hmm…something like AWS…before AWS existed. I mean, AWS was technically available in 2009, but it was nowhere near as user-friendly as it was today. Slicehost allowed developers to set up hosting using a beautiful GUI (at least according to 2009 standards). Patrick used Slicehost for all of his side projects and the guy was absolutely starstruck with it.

There wasn’t an “aha” moment for Stripe. Sure creating merchant accounts was hard and archaic at the time…but monetizing side projects wasn’t top of mind for the teen millionaires. It was just this fascination with the new phenomenon of building an abstraction layer around something so boring and complicated- as was the case with Slicehost- ….and turning it into something that is intuitive and easy to use that excited Patrick. He figured he could replicate the Slicehost model for payments.

Hacking away at Buenos Aires - Winter Break (Jan 2010)

In a parallel universe, John completed his high school back in Ireland and received the highest score ever in the country's history. It should come as no surprise that John got admitted into Harvard, and so the duo were both in the US doing boring school stuff and primed for round 2 of building a company together🥂.

Leading up to the Winter break, the Collison brothers applied and got into YC (again) and officially received their funding of 20k-30k by January 2010. Instead of going through the program…they decided they wanted to "hack at it" away from all distractions in the beautiful city of Buenos Aires @ Argentina.

Getting their first user

Bear in mind, Patrick and John, despite their very young success, still had no freakin clue how the financial industry worked…what they knew was how to code.

So what they did was … lie (is it lying if no one asks, though ? ). There was no “financial infrastructure” in any way for the first two years of Stripe. Patrick had a friend working at a payments gateway company…the company’s API was pretty horrific to set up and deal with. So Patrick and John created a set of APIs that were a lot easier to use; he abstracted the whole thing to 7 lines of code that any developer could copy-paste in under 1 minute.

On the backend, when someone signed up to Stripe, Patrick called up his buddy, gave him the details and his buddy set up a merchant account for that user. Stripe just turned those 🤮 APIs …into something a bit more comprehensible and faster to implement. It wasn’t a payments company or anything at the time.

The first customer of Stripe was a friend of Patrick and John from the early YC days, “Ross Boucher.” Ross was the founder of a Web software development company named 280 North. He also became the first employee at Stripe. In my book, it’s a pretty darn good signal when your first customer leaves their company to join yours after only trying the beta version of your half-baked product.

Fun facts:

The Powerful analytics screenshot…was actually from plane-related mailing list that Patrick subscribed to…it had nothing to do with Stripe.

Their pricing page was “We’re finalizing our pricing right now, we’ll be competitive.”

The company at the time was named /dev/payments. There is a whole thread about how they came up with the name Stripe..you should check it out 😁

Getting the first 20 users.

The subsequent 20 users followed suit...all were other YC companies. There are many arguments about whether you should recruit your first users out of people you know (and risk getting sugar-coated feedback) or recruit people you don’t know (who are just a lot harder to find.)

Not only did Stripe lean into people they knew….they were also extremely aggressive about it. As Paul Graham outlined in his essay Do Things that Don’t Scale

“At YC we use the term "Collison installation" for the technique they invented. More diffident founders ask "Will you try our beta?" and if the answer is yes, they say "Great, we'll send you a link." But the Collison brothers weren't going to wait. When anyone agreed to try Stripe they'd say "Right then, give me your laptop" and set them up on the spot.” - Paul Graham

Pricing as a forcing function.

Feedback is crucial in the early days of any company, especially a company attempting to solve such a complex problem like the one Stripe was after. The right feedback could make your business but the wrong one could detrimental to the company. Getting candid feedback is tough when all your Beta users are your friends and colleagues.

Patrick and John decided to price Stripe during Beta at the most expensive end of the spectrum 5% +$0.5 when all their competitors were charging 2.9%-3.2% + $0.3. This expensive pricing structure ensured 2 things:

- People who signed up to Stripe and were willing to bear the expensive cost were not incentivized by money. Money creates all sorts of conflicts and may very well attract the wrong customers. You don't want to be building for the wrong audience ever...but especially not in the early days and not in an industry where product decisions are almost irreversible.

- It also forced the team to build a great product. The more you charge for your product, the higher the customers' expectations are. Having that pressure from customers asking every day if their offering was truly worth almost X2 what the competitors charge, ensured that the only way to keep their customers around was to build a product that was at least twice as good as anything out there (and that was not an easy task considering Paypal was one of their main competitors)The next 50-100 customers.

Despite their initial success and raising some money from YC…both John and Patrick went back to school to finish off their sophomore and freshman year, respectively. They looked at Stripe as a side project and it wasn’t until six months after they acquired their first customer that they had enough conviction to pursue this full-time and drop out (yet again).

The realization, according to Patrick was something along those lines..

“ (we realized that) the economic foundation of the web was really shaky and despite Paypal’s best attempt…they never really got there. The internet is still very young.....still a small fraction of transactions happen online. It’s crazy how manual it is...it’s incredibly hard to transact across borders…. if you are an American you can only buy from American companies and so is the case regardless of where you live. There should be robust reliable economic layer of the internet...and we really felt like we could solve that”

As the summer started reigning in and the Collison brothers took Stripe more seriously, they did a few things to begin acquiring customers outside the YC circle.

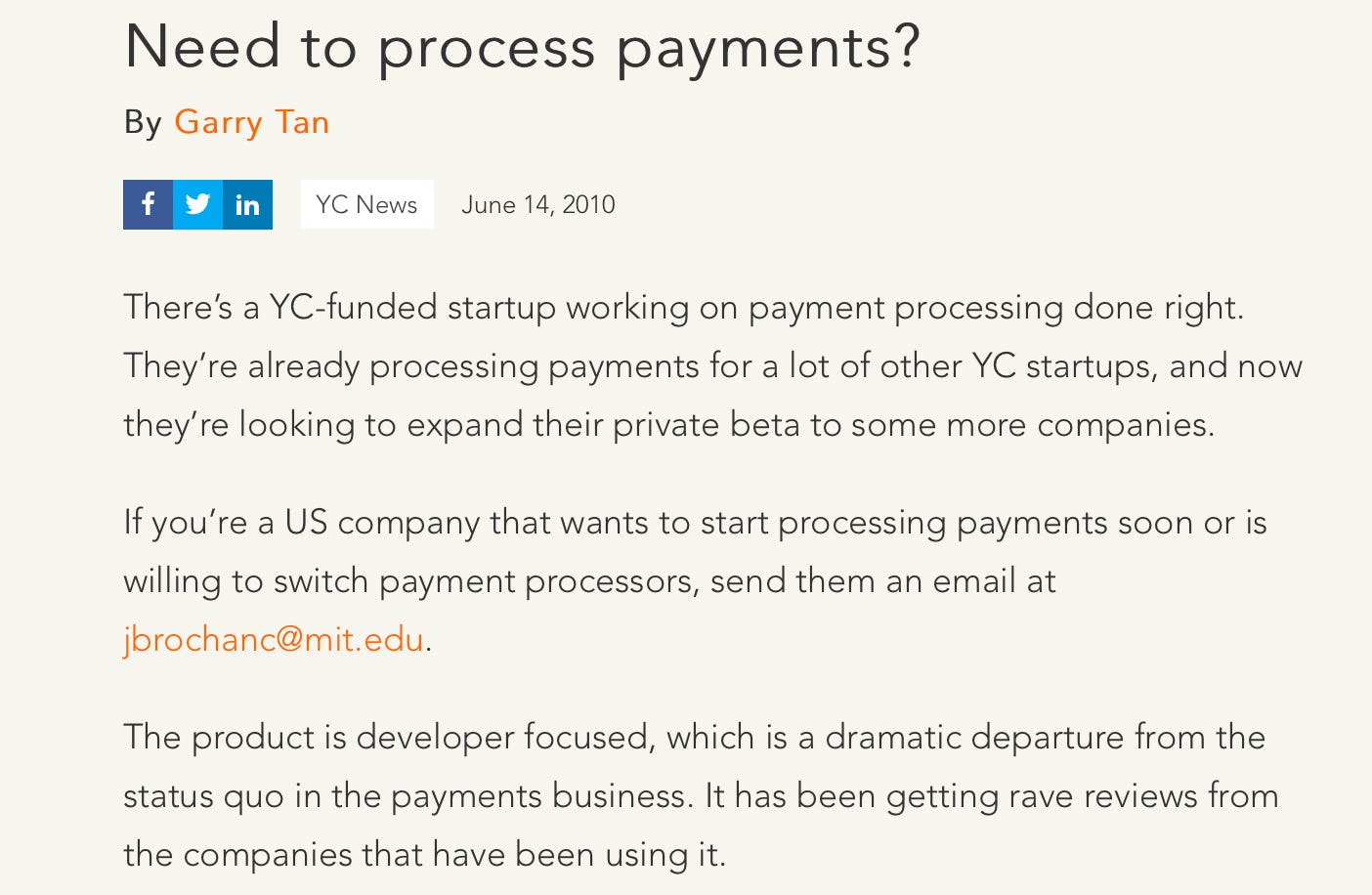

The first thing they did (they didn’t do that but rather Garry Tan, who was a YC partner at the time) was to launch a request for the team on HackerNews. The request was if you need payments on the internet..drop those smart people an email and they will help you out. By my very unscientific method, this post landed them between 300 and 550 signups on the waitlist. (Stripe had to implement a waitlist because… they had to do all the account creation stuff manually)

Swag-on: Every time someone made their first transaction on Stripe, they sent them a Stripe swag kit. (It helped that they had the addresses of everyone signing up handy)

Employees: This was not something the brothers planned on. The duo was extremely young (19 & 17) when they founded the company, so every new hire needed to take on a lot of responsibility. Naturally, they leaned into hiring founders. Out of the first 10 employees, 8 of them were founders. If there is one thing you can bet on….it’s that founders know other founders (period)

I want to take a moment to say that sending Swag and writing a post on HackerNews is not the almighty-secret-recipe to success ( I am sure you already knew that 🥶). The primary reason it worked for Stripe is that, counterintuitively, selling a payment gateway is much easier than selling the majority of other products (many of which you may be working on). There are a few reasons for that:

- People know that payments is something they have to deal with; it's not a maybe question; it's a "which one" question. Payments is fundamental to every business.

- People associated payments with pain. "Payments for developers that doesn't suck" became the new mantra (As a refresher…when Stripe first started, they were aspiring to be the “Slicehost for payments,” but that messaging didn’t quite stick)

There are a minuscule number of infrastructure products that you need to use regardless of the product you are working on and where the only real alternatives are cumbersome 1997 legacy companies. If you are lucky enough to be working on one of those, then you don’t have to find people that need your product …cuz everyone kinda does (which is 90% of the work). You only need to prove you are better than what's out there.

In that case, shooting your shot at someone coming across your brand name via a blog post or some swag they saw a random dude wearing at a Hackathon may be your best approach.

But if you are working on a consumer product, you may want to do the exact opposite…and narrow down on tiny concentrated circles of users and acquire the most significant portion of those as you possibly can (see the case studies on Udemy, Slice or Snackpass)Raising money and actually building the product.

By the end of the summer, Stripe accumulated around 1000 signups to their waitlist. It's not clear how many of those were in the beta, given that Stripe had no financial infrastructure. If I am to bet my life on it, I would say something like 50-150 users. After the summer of '09 concluded, John and Patrick decided to go full time on Stripe. They raised $2m from whose who in the tech circles… that includes A16z, Sequoia, Elon Musk, and Peter Thiel.

Patrick attributed much of their ability to raise this money to Paul Graham, who facilitated many of these intros and was a grand champion of the company. Over the following 14 months, the team laid low and went full-on building mode. They got the appropriate partnerships in place, dealt with regulatory requirements ..etc..etc

On September 29th, 2011….Stripe finally launched to the public.

Getting Customers Post Launch

In the post-launch era, Patrick and the team started pouring more energy into acquisition:

Every month they hosted a Capture The Flag contest (think of it as Minecraft for engineers) at their offices. According to the one friend I talked to that attended one of those…he loved it! Free pizza and drinks were flowing…(and who doesn’t like free food).

As the team grew and more people started attending those events, the group began doing meet-ups. If John or Patrick were in another state for one reason or another, they would put together a meet-up event for developers and hackers. In the beginning, these were Capture the Flag competitions, but over time morphed into a more general meet & greet kind of events.

As the interest in Capture The Flag competitions grew further. They started hosting them online….thousands and thousands of developers tuned in to solve these challenges every month.

Within six months, they started running ads on StackOverflow. For the first year, that was the only channel they used for paid marketing.

They also really really leaned into the narrative of “Paypal founders backing the next payment internet company.” See here and here

The last bit was reviews from internet bloggers. For the most part, those were unsolicited (example, example2) but were a cornerstone to how they acquired customers post-launch, according to a random 2012 interview with Patrick I stumbled upon.

I would hate it if the key takeaway here was to host competitions or god-forbid gamify your app. Personally I am an adversary of gamification but that is a story for another day 🙈. The biggest insight from Stripe's approach, for me at least, has been how they layered in their marketing effort. In most places I have worked in the past, marketing is a one and done exercise. You come up with an idea, put some $$ behind it, measure your performance and then put some more $$$$ behind it (maybe experiment with a few messages along the same theme). What Stripe did was that they evolved their marketing, adding in more value and complexity as they grew, just as any good product person would do to their core product. Of course, this was possible because their marketing- in the form of these Capture The Flag competitions- was something valuable to the users. But this is not unique to Stripe. Many companies, especially those in the financial industry, build tools, calculators, or even content as a core part of their marketing. More often than not, those are treated in a "let's see what sticks" manner. They are not nurtured and handled with the same user empathy, and thoughtfulness one would provide their core product. This is what I believe Stripe did differently, and the results do kind of speak for themselves 😁.

Until we meet next week,

Ali Abouelatta