🚗 Waze

How Waze got started

Hello Frens 👋,

For the first 10k-15k readers of first 1000, I sent out an email after someone signs up asking them what companies they would like me to cover. The ended up with a backlog of 700-800 companies.

On the very top was Waze, the company that dared to (successfully) compete with Google on the home turf: Maps.

The day is finally here, I recruited Jacob from Making Product Sense to guide us through the journey of Waze.

As Ali and I were talking, he mentioned that since the beginning of First1000, he’s been collecting an ever-growing list of companies that readers have asked him to write about. And toward the top of that list was none other than Waze.

As a user, I’ve been a fan of their quirky design and gamified reporting for years so when I started breaking down world-class products for Making Product Sense, I knew at some point, I would have to write about Waze if only to appease my own curiosity.

So without further ado, let’s dive in.

When Waze started in 2006, mobile navigation apps were effectively non-existent. At least not on a smart phone. The first iPhone wouldn't launch for another year and the smart phone market was dominated by Blackberry, Nokia and Motorola.

While there were some mobile navigation apps on the market like Nav4All, Google Maps and Apple Maps didn't exist yet and many people still relied on the standalone GPS devices that suction cupped to your windshield.

So when Ehud Shabtai, Amir Shinar, and Uri Levine set out to create a mobile navigation app in Israel, the expectation wasn't to become the next Israeli tech unicorn. It was simply to create the best app that will get you from point A to point B in the shortest amount of time possible.

Except there was one problem.

Maps are expensive.

If you wanted to offer a mapping service, the most expensive part, by far, was the license for the map itself. In 2006, it was effectively a duopoly, with Navteq (acquired by Nokia in '07) and Tele Atlas (acquired by TomTom in '08) owning the two largest sets of base data for maps.

"If you want to go out and buy a map today for navigation, you can't. There's OpenStreet Map which is an open-sourced map which has several advantages and disadvantages. Google has its map and not selling it. Nokia and TellyAtlas have their maps and they're very expensive if you want to buy them. And Apple doesn't sell its maps. So you can't really get raw data and so for us, owning the raw data was crucial.”

—Noam Bardin, former CEO of Waze

And the reason was that it was ridiculously expensive to collect map data. Even to map one street, you have to drive it with GPS tracking so it can gather the actual coordinates of the street and then spend time labeling the:

street name,

city, state and country it's in,

intersections with other streets,

lane count,

lane merges,

stop signs,

traffic lights,

and speed limits.

And that's just for the base map. We haven't even talked about addresses, parking lots, bridges, toll booths and other points of interest that drivers will expect. Now, just do that on a national (and eventually global) scale and you're looking at hiring thousands of drivers, purchasing thousands of vehicles, investing thousands of man-hours and paying for thousands of tanks of gas just to get your base map before you can offer a single scrap of value to your end users.

Like I said... maps are expensive.

Crowdsourced Maps

I don't know whether to chalk it up to blissful ignorance or blind optimism, but despite the overwhelming odds against them, they decided to take a stab at creating their own maps. And as the saying goes, necessity is the mother of all invention. Their thesis was that they could get enough people to volunteer to "pave" the roads of their map by driving around throughout their normal days and letting Waze track them via the GPS chip in their smart phone.

Just a Blank Map

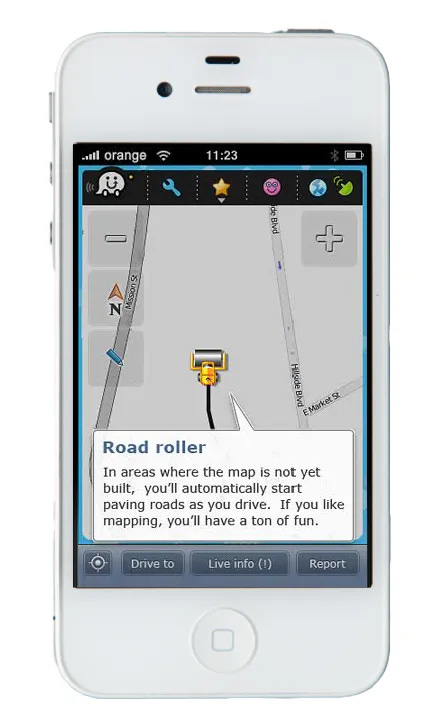

Surprisingly, there actually were enough map nerds in Israel who found it fun and interesting to be a part of the grassroots team mapping their country. To participate, they would download the Waze app and were greeted with a blank map. As a side note, can you imagine how odd that UX must have been for some users? A blank map? Wild. But these folks would then drive around and let the app capture the GPS data from their phone. Then, back their house, they would plug their phone into their computer and manually label the streets, filling in dozens of meta data points for each one.

"If you were the first user in a country and you installed Waze, the map would be empty. A blank canvas. You'd start driving and your icon would turn into this road roller and you'd start paving a road that you'd see being created behind you. And that was the first road in that country. As you drove, more and more of these roads began connecting.

Then you'd need to go online to our editor - a web-based application - from your desktop or laptop, not from your phone. And you'd need to begin giving a name to the road and you'd need to play with the geometries a bit because the GPS reading wasn't accurate. And you'd connect two roads together as an intersection. Do you have a right turn or not, was it one way or two way, what city was this road a part of etc. So there was a lot of meta-data you'd have to add in. To do this, we needed a relatively small number of highly engaged users that would do it with us and then they'd build out this grid.”

—Noam Bardin, former CEO of Waze

Real-time Data

Remember how I said this was just the base map? If you think about a navigation app, you'll begin to realize there's so much more data that needs to be gathered once the roads are marked. Data such as traffic patterns, how long it takes to drive a particular segment of road and speed fluctuations due to terrain. That data could only be accumulated over time with hundreds, if not thousands, of people driving the same routes every day, building up layer upon layer of historical data and insights.

“So now you have this grid. Now you need a lot of people - more people - to drive on this grid. Because as they drive, we're learning directions, we're learning speeds, and we begin building this historical database of speeds, how long does it take to drive each segment. So for that you need more users driving around, still getting no value. So we built a gamification platform using points and virtual goods to allow a larger percent of users to come and play."

—Noam Bardin, former CEO of Waze

And this is where I believe Waze started to have a snowball's chance in hell at succeeding in a world dominated by legacy mapping companies and crappy apps. They had just built a tight-knit community of a couple hundred volunteers who agreed to drive around with a blank map open and spend precious hours of their nights and weekends labeling the nameless streets. Clearly, they had something special. A community.

As the map of Israel began to take shape, why break up the band? Why not lean into the best thing they had going for them and let the users themselves continue to refine the map?

Participation Inequality

In social apps, there's a principle called "Participation Inequality" which posits that 1% of users are active creators. They produce the lion's share of the content and are the driving force behind the community's life and engagement. Then there's another 9% of users who contribute occasionally, posting, commenting, and liking. And then there's the 90%. These are the consumers who are only there for the memes and don't actively contribute to anything.

Waze noticed a similar pattern begin to emerge. The mapping super-nerds were the 1%. They actively helped create the very map itself. Then there's the 9% who are the mapping enthusiasts. They won't drive with a non-existent map, but they're excited enough about the mission that they'll drive with a buggy map that occasionally routes them down a dead end. And finally, the 90% who will show up after the wrinkles have been ironed out and Waze can actually deliver on its promise of getting you to your destination as quickly as possible.

In this 9% stage, Waze built out a gamification layer to encourage users to help participate. The intrinsic motivation that drove the 1% of users to "pave" a blank map just wasn't enough for the 9%. But if they can contribute to the project while earning points they could spend on virtual goods? Now we're talking.

Human-powered Reporting

That brings us to the third level of data. Waze's secret sauce. The human reporting.

In 2009, they brought on an experienced CEO to run the company named Noam Bardin.

"Bardin cited issues with the navigation, an example of the app pointing a route that would make a driver jump off a bridge and onto a highway."

But despite the issues, there was something special about Waze that made him want to take the job. The first time he watched his wife use the app, she remarked, "I don't feel so alone." Sure, the maps weren't 100% navigable yet but... they could make you feel something. And seeing others in your community working toward a common goal was a beautiful experience.

The Emotional World of Traffic Reports

So Noam decided to lean into their ability to make an emotional connection with their users. In the early days, when you stopped at a stoplight, they would show you traffic reports from other users. But since they didn't have the density needed to show a bunch of relevant reports nearby, they showed you reports from the nearest 10 Waze-ers. No matter where they were. At times, divers in San Fransisco would see traffic reports from New York City.

Since they had begun to expand beyond the initial 1% and 9% of users and into the consuming 90%, this obviously upset a lot of folks. They would complain in the App Store reviews and forum threads about the irrelevant traffic reports but, despite that, the Waze team didn't change it. Because at our core, us humans like to know others are with us, using the same crappy app that we are and submitting the same traffic reports that we are because it's the helpful thing to do.

Google Launches Google Maps

After the Google Maps mobile app launched, the Waze team had a mini-melt down. Google was the behemoth that could squash Waze in an instant. They had the distribution, they had the resources, and most importantly, they had a crazy good product. But in hindsight, Waze had something special that Google just didn't have. Their super-fans.

Today, aside from navigation itself, the core mechanic in Waze is the reporting feature which allows drivers to report traffic, police, accidents, hazards, gas prices and road closures with a tap. Reports from users will show up on the map and prompt other drivers passing by to confirm the report, creating a real-time data layer on top of the traditional navigation app experience.

"We believe as a matter of philosophy that you need to combine humans and algorithms. Neither of them is a slam dunk. But working together you can do crazy things."

—Noam Bardin, former CEO of Waze

Their users are their secret weapon and have been since day one.

"Tim Cook Day"

Fast forward to 2012 and Apple releases their Maps app, replacing Google as the default navigation option on the iPhone. And for a moment, it seemed that Waze would be going up against two of the biggest tech giants the world had ever seen.

Except that Apple screwed up.

They released a severely unfinished version of Maps and the world erupted with criticism. It got so bad, that Tim Cook did something that shocked everyone. He apologized and suggested that folks temporarily download another navigation app until Apple can get their sea legs under them.

"You can try alternatives by downloading map apps from the App Store like Bing, MapQuest and Waze, or use Google or Nokia maps by going to their websites and creating an icon on your home screen to their web app."

—Tim Cook, CEO of Apple

This plot twist made Waze's user count skyrocket by 40% up to 50M users. Supposedly, every September, Waze employees still celebrate “Tim Cook Day”.

The Road to $1,000,000,000

As they rose in popularity on a global stage, they began to get noticed by the other companies building navigation products. Apple, Facebook and Google all started sniffing around. You might be puzzled by the last name on that list. In 2012, Google already had a 50%+ marketshare along with the resources and platform (Android) needed to distribute globally. Why would they want to acquire Waze?

If I had to take an educated guess, it would be the thing that's allowed them to exist since the beginning. A loyal community who's willing to devote incredible amounts of time and care to building something great. A product for the people, by the people.

Google is in pursuit of organizing the world's information. And Waze had the best and most real-time map information on the planet, powered by the one thing that Google has tried to supplant with software. People.

The next year in 2013, Google acquired Waze for somewhere between $1.1-1.3B.

Takeaways

In case you imagined that Waze “grew up” and abandoned their early practice of allowing their users to edit the maps from their computers, don't be fooled. Waze has absolutely doubled down in the most incredible way and, today, the Waze community is more vibrant and more active than ever.

Anyone can log into the "Waze Map Editor" and suggest edits commensurate with their rank. (Oh yes, they have ranks. And badges. And MapRaids.) After stumbling down the rabbit hole of Wazeopedia, I found a lovely slide deck that goes through the ranks in detail. I won't belabor it, but to help you understand the level of commitment we're talking about here, to earn Rank 6 you have to submit 500,000 map edits.

To me, that perfectly illustrates the magic of Waze.

Let the 1% help you build. They're probably more willing than you think.

This is like the extreme version of the startup mantra, "talk to your users." And it takes a fairly radical mindset shift, because you can't yank the product back after you've let them help you build it. If you embrace your community early on, you need to embrace your identity as a community-led company.

Reward the 9% for their efforts. They just want to know they'll be recognized.

These users want to give their feedback, but they don't want to put in the work without being acknowledged. Consider how you might incentivize or reward them. Even something like a badge next to their name that denotes them as an OG user could go a long way.

Make the 90% feel something. Sometimes, emotion is more powerful than utility.

Waze makes you feel like you're part of a secret, elite team that's fighting against the evils of traffic. If they can take a relatively mundane use-case like navigation and turn it into a playful, social-product, that goes to show just how powerful emotion can be. Position your user as the hero of the story, identify a common villain and give them the weapons to fight against it and they'll love you for it.

That’s all for this one.

—Jacob ✌️

Shoutout to Ali for giving me the opportunity to write for you guys! I’ve been reading First1000 since the beginning like many of you, so it’s an honor to get to give back in some small way.

If you’re interested in product deep dives like this one and interviews with world-class founders, I publish weekly over at, Making Product Sense. I’d love to see you there :)

Thank you for sharing your research and analyses with all of us here @ First 1000. You can find Jacob on Twitter, or over at Making Product Sense

Until we meet next week,

Ali Abouelatta