Hello Folks 👋,

Around two and a half years ago, after reading Andrew Chen's series A investment memo, I first became aware of an exciting new newsletter publishing platform, Substack.

Like I do with any new company A16z invests in, I signed up. In part to reserve my domain name and in part out of curiosity. But the thought of actually starting a newsletter never crossed my mind.

Fast forward a year later. It is Covid time. I'm locked in my old bedroom, with 4 months remaining to start my Master's program. I had more time than I knew what to do with.

Throughout the lockdown, the idea of writing a Substack about getting your first 1000 customers took shape. By the end of May, I published the first case study on Roam Research, followed by Doordash.

At the time, Substack was still relatively new. Yesterday the company crossed the 1,000,000 paid subscribers mark.

What is Substack?

Substack is the platform that powers First 1000 and thousands of others.

Substack handles everything from analytics to subscriptions (for paid newsletters) and even customer support. I, in return, am freed to do the one thing I set out to do: writing.

I had a chance to sit down with Hamish to talk about everything Substack. From the genesis to the media landscape to how they built products.

Today, I will be discussing:

Origin Story

Market Dynamics

Go To Market Strategy

The First 1000 Customers

Substack: the Product

Moat & Defensibility

Current Traction and Opportunity

Risks

Origin Story

The people

Chris Best, Hamish McKenzie, and Jairaj Sethi started Substack in 2017, but their history dates back years before.

Chris co-founded the anonymous posting app Kik during his third year at the University of Waterloo (2010). He spent the better part of eight years at the company where he met his soon-to-be co-founders.

Before joining Kik, Hamish spent just shy of two years at Sarah Lacy's tech publication Pando Daily. One of the companies he covered regularly was Tesla. In 2014, Hamish got the attention of Elon Musk and joined Tesla as its lead writer.

A year later, Hamish left his Tesla job to write a book about his experience Insane Mode. While working on the book (2015), he joined Kik on a part-time basis.

Jairaj, the third co-founder, joined Kik straight out of the University of Waterloo in 2012 (where he overlapped with Chris). Jairaj spent almost 6 years at Kik before co-founding Substack with Chris & Hamish.

The Idea

When Chris left Kik in early 2017, he wanted to spend time enjoying the simple pleasures of life that he previously didn't have time for. This includes spending time with family and friends reading and writing.

From Chris's point of view, writing was one of the highest leverage use of his time; through writing, he believed, authors could change peoples' worldviews, impact how they think, and see the world.

The first essay Chris set out to write was on the current state of our media ecosystem. The essay was shaped by his 8-year journey running an anonymous social media app that peaked at over 300m registered accounts.

Chris shared early drafts of the essay with Hamish. Hamish did not find the essay as inspiring as Chris hoped he would. He proceeded to explain that the problem was obvious, the solution, on the other hand, was not.

Hamish and Chris started riffing on how to solve the problem:

Could you fix it by changing the algorithm?

Could you censor your way around it?

The answer to both these questions was a clear No. The underlying problem wasn't the algorithm not doing its job correctly or that moderation efforts were nascent. It was that they were doing an outstanding job at what they're supposed to: getting users to spend more time on the app.

The Angle

To fix the current state of media, they hypothesized, you must change the business model from one that optimizes for your time to one that optimizes for your money.

Market Dynamics

It is hard to understate the impact social media had on how content is created and distributed.

Social media dismantled publications into articles, with each piece competing for the attention of readers against:

User-generated content

Articles from competing publications

Articles from the same publication

As an author, to be competitive on social media, I am faced with a tough decision: I could either increase the frequency of articles I publish or increase the virality potential of each or, ideally, both.

However, these objectives are entirely disconnected from what I strive to do; being a great writer.

A hypothesis for this disconnect (and the guiding principle behind building Substack) is the shift around how we value attention. Attention quickly went from being one of our most abundant resources to one of the most scarce ones. Before Web2 and the emergence of content aggregators, we needed pass-time activities like baseball, and throughout the mid to late 2000s, social media emerged and gobbled up everyone's attention.

As this flipping of attention took place, our content consumption diets deteriorated.

It is no secret that social media algorithm optimizes for reach and engagement. The content that captures the highest reward possible on the platform "virality" is the one that optimizes for the lowest common denominator.

Additionally, the decision of clicking or reading an article is seemingly inconsequential at the moment (although incredibly impactful in aggregate).

The social media reward mechanics and the inconsequentiality of playing the game contributed to the increasingly sub-optimal decisions we make on what to consume at any given time.

On the other hand, as time spent consuming sub-optimal content increased, so did the perceived value of high-quality content.

Platforms and experiments emerged in the early 2010s to validate the market desire and increased willingness to pay for higher quality content. Hamish and Chris highlighted many of those as they introduced Substack to the world in 2017:

We believe strongly that people will pay to read high-quality stuff about the subjects and people they care most deeply about. But thanks to Patreon and a nascent pre-Substack subscription publishing movement, it's also clear that a significant number of people are willing to pay good money for podcasts about war history, YouTube shows about video game critiques, in-depth NASCAR reporting, bodybuilding, and many other niche interest areas.

- Substack Announcement Post

One of the most prominent examples of this phenomenon is Ben Thompson's subscription publication Stratechery. Stratechery covers the intersection of technology and strategy. Ben ran a highly successful one-person media business through a combination (at the time) of WordPress, Mailchimp, Memberful, and other plugins. Many speculated he was making in the realm of 7 figures at the time.

Ben's phenomenal success was no secret to the tech world. He consistently wrote and explained his hypothesis of the rise of narrowly-focused niche sites that build a sustainable business on the Internet. Still, three years into Stratechery, there were only a handful of people emulating Ben Thompson's success.

Why weren't there more? Perhaps because it was freakishly hard to make all the moving pieces work together.

Go To Market Strategy

A fundamental principle of competitive advantage strategy is new products compete on only two dimensions: Differentiation or Cost.

In media, differentiation would most likely encompass a coverage niche. Cost, on the other hand, is a little bit more complex.

For an ad-driven media publication, the lever a publication exercises most control over is distribution cost: how much does $ is spend to generate one article view.

Customer Lifetime Value and revenue, while dictated partially by the quality of an audience, are primarily driven by external factors outside the publication’s control.

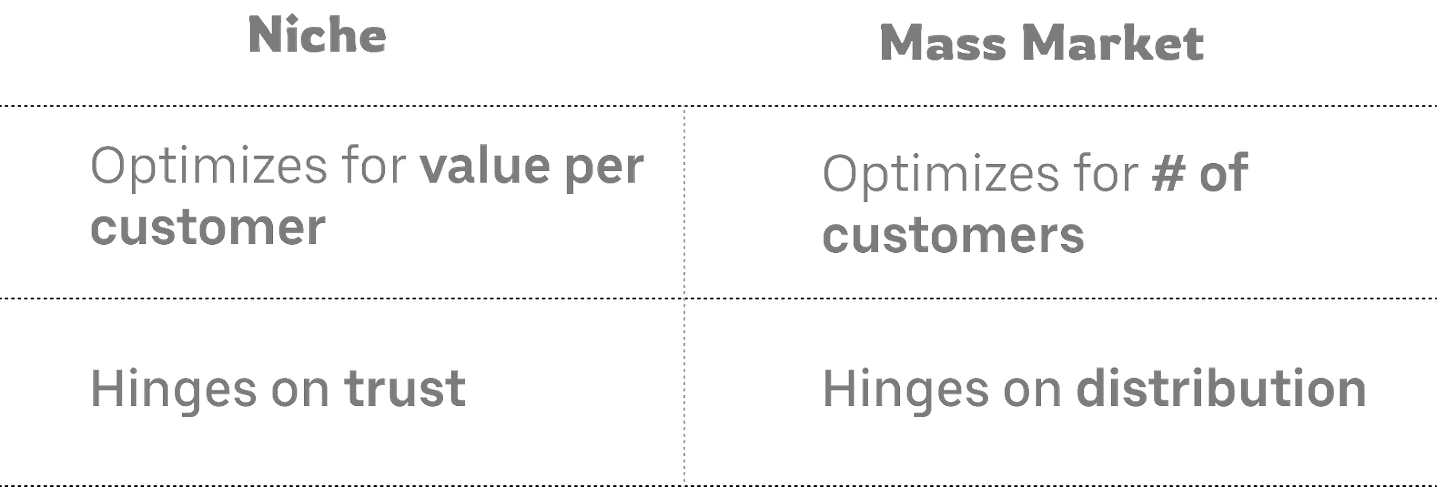

The bet Substack made was the rise of media businesses competing on the differentiation axis instead of the cost one. A niche media business differs from a mass-market publication on a couple of levels:

To maximize value creation for each writer from the very early days, they built the first Product for just one person: Bill Bishop, author of Sinocism.

The first 1000 customers

Customer 001

Hamish knew Bill Bishop from the days he lived in Hong Kong before joining Pando Daily. Bill, at the time, lived in Beijing. He started a weekly newsletter that provided commentary and curation around the important news in China named Sinocism in both English and Chinese. That was back in 2012.

Hamish wrote a profile on Bill's influence on China-US Relations soon after joining Pando Daily.

Five years later into Sinocism, after numerous conversations with Ben Thompson, Bill decided to switch to a paid subscription model and planned to launch the paid version in the spring of 2017.

Due to unforeseen circumstances, he had to delay the launch by a few months, and in the fall, just before he planned the launch, he got an email from Hamish reading something like:

Hey Bill, we're making this thing called Substack, it'll be a very simple way to do a paid newsletter, would u be interested in being the first publisher?

-Hamish recounts

Bill figured he would be better off having Hamish and Chris help him out rather than try to do this thing on his own.

To build the very first version of Substack, Chris and Hamish flew to Washington, D.C, where Bill was at the time. They built a product exclusively for him. Small scope, large impact.

This approach led to discovering and building features that may have otherwise seemed like a post-MVP thing. A most prominent example of this was building group subscriptions in the very first version of the product.

In October 2017, Bill enabled paid subscriptions for the very first time to his 30k+ subscriber base. By the end of launch day, Bill had already brought in six figures of yearly revenue.

A few months later, Bill became an angel investor in Substack.

Customer 002

Hamish and Chris continued with the same approach, recruiting already established writers and solving the needs of their acute publication in a generalizable manner.

The second writer they onboarded to the platform was Kelly Dwyer, who started The Second Arrangement. Kelly has long been regarded as one of the most influential internet writers in the NBA sphere.

Customer 003 Onwards

Every new writer that joined the platform provided two distinct opportunity media opportunities to Substack:

The first round around {well-regarded} writer going independent via Substack

One around Substack- the platform landing- {well-regarded} writer

One of the most prominent early examples of this media coverage was right after Kelly decided to join Substack. Hamish convinced Jack Marshall from WSJ to write an article about Substack two weeks after the first publication on the platform, which Vox and Techcrunch already covered.

A month later, Mallory Ortberg revived her publication The Toast on Substack. Fast company covered the event.

It has been 4 years since. And the media coverage of new writers starting Substack publication hasn't shown signs of slowing down.

Substack the Product

To understand how Substack attracted some of the highest-caliber online writers from the get-go, one must first understand the product and its philosophy.

Substack did not sell a better product. They sold trust. What differentiates their product is the degree of alignment between the company and the writers:

It takes less time to export your subscriber list and leave the platform than it does to join

Substack charges a 10% commission on paid subscriptions.

By focusing on creating a writer-centric platform, Substack gained trust amongst the most established writers. Here are a few product features to highlight the extent to which Substack went to establish trust with writers:

Writers on Subtack own the end-to-end relationship with their customers.

Writers can leave the platform as quickly as they join.

Exporting metrics and subscriber lists are only one click away

Substack is free to use, regardless of subscriber list size.

The only way they make money is if a writer starts a paid publication. The only way for Substack to make a lot of money is if writers on the platform make a lot more money.

These features increased the speed of the adoption of the product. By lowering the perceived risk of a product and growing tolerance for errors, Substack was able to gain the trust of some of the most renowned writers on the Internet and convince them to start a publication.

They had very little to lose and everything to gain.

Moat and defensibility

Substack’s moat is hard to grasp at first; they built a product that lacks any sort of writer lock-in. The lack of platform lock-in, in fact, is one of the core value pillars of the product.

Despite the lack of lock-in, Substack still enjoys a variant of network effects. One that is not centered around product features but rather around relationships.

As discussed earlier, the critical value proposition for Substack centers around trust. The more prominent writers trust the platform and move their audiences to their Substack publications, the more trust Substack- as a platform- develops with end-readers.

In turn, this high degree of trust makes end-readers of a particular Substack publication more susceptible to subscribing to other Substack publications.

This cross-pollination between newsletters on the platform only needs to account for 10% of paid subscribers for writers to break even on the Substack fees.

Current Traction and Opportunity

Bill Bishop, along with Substack, recently celebrated their 4th anniversary along with a major milestone

Today Substack celebrates over 1m paid subscribers 🎉

While the product has dramatically evolved since the early days, it still embodies much of the same ethos: it is built on trust and value creation for writers. The most significant and most obvious opportunity for Substack is expanding its discovery efforts. Beyond that, there are several pockets of opportunities for Substack to explore:

Curated matchmaking w/ service providers. I presume that helping creators find the right designers, editors, and marketing expertise would be a welcomed addition to the platform.

Interpolarity with other media formats. Having Substack be the "home of the content creator" rather than the "home to the creators' newsletter." Many exciting mechanics and use cases arise from a writer's ability to sync their podcast, interview appearances, and youtube channel. to their Substack writer's profile

Content consumption. Content consumption is still primarily broken, and for the many benefits that email provides, it still falls short on my respects.

Risks

The main risk I see for Substack is the reliance of authors on social media for distribution. My guess would be somewhere around 15%-25% of all new subscribers to Substack publications come from social media platforms.

With Facebook, and Twitter launching (or acquiring) their newsletter products, it is possible that they artificially hinder the distribution of any post linking back to a substack publication to make their products more competitive when failing to compete on merits. Something they have done repeatedly in the past.

Substack is built uniquely around the needs of an individual creator running an independent business. Collaboration and small-team publications can still be powered through Substack, but as (or if) these publications become larger and larger, there is a tradeoff to be made on the ease-of-use v.s complexity that arises from building enterprise(y) like features to support these mid-size publications.

--

Substack is an exciting story, with trust intertwining all aspects from Product to strategy to customer acquisition.

If they lose that, almost nothing else matters, and from my experience interacting with the platform and the team, it doesn’t seem like this would be the case anytime soon.

Until next week,

Ali Abouelatta